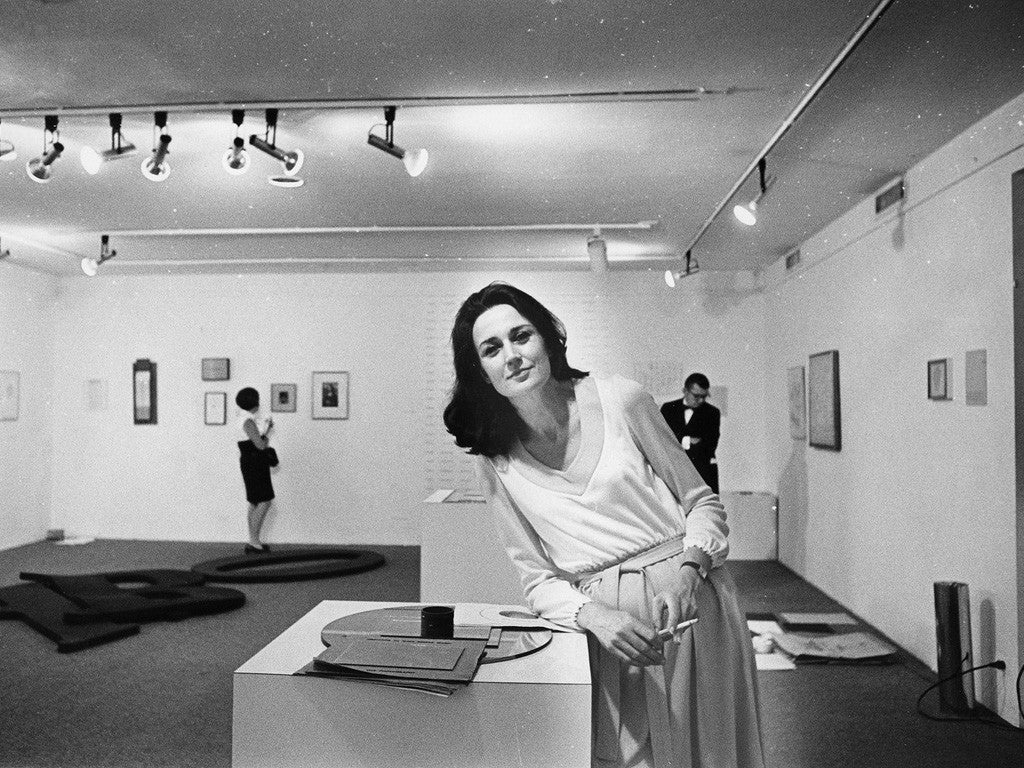

After climbing a staircase of heavy wood and ironwork in a storied apartment building on the Upper West Side, visitors to Virginia Dwan’s rooms are confronted with cool cream walls and an array of minor masterpieces from the ’60s and ’70s. Strands of minimalism prevail, starting with a black-on-black painting by Ad Reinhardt. Beneath one of Sol LeWitt’s modular wall structures sits an Arabic prayer rug. “If you were in the art world you had oriental rugs,” Dwan explains. In it she was, as “Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971,” at the National Gallery of Art’s newly renovated East Building, attests.

Featured conventional watercolors

Struck by what she saw at the Walker Art Galleries in her hometown of Minneapolis, Dwan went to UCLA to pursue fine arts. She was told collage work was no way to make a living, and began helping Frank Perls, the son of German art dealers (Picasso was a family friend), with his own gallery in Beverly Hills. Dwan would open her own gallery, in what had been a men’s clothing store in Westwood Village, a few years later, at the age of 28. Her first show may have featured conventional watercolors, but she soon found her footing in a predilection for the avant-garde, which at that time meant nouveau réalisme. It was in Paris that Dwan saw her first Yves Klein, hanging in a gallery window. “I went back the next day and arranged for a show of his work,” she says. And so that famous blue arrived in the States. Klein introduced her to John Tinguely, who left Leo Castelli’s roster to join The Dwan Gallery, suddenly L.A.’s arbiter of important French art.

Dwan went on to place herself at the forefront of a wide array of movements, from Pop—she was the first to show Warhol’s Brillo Boxes—to Minimalism to Conceptualism to Land Art. “Art history has validated her taste,” says James Meyer, who curated the exhibit at NGA before joining the Dia Art Foundation as chief curator and deputy director. In 1965, Dwan opened in New York—“to be in the center,” she says, though the show underscores a decentering, or at least an increased interconnectedness, as oft-traveling artists traded ideas between coasts and countries. With her two galleries, Dwan “gave a forum for that kind of exchange,” Meyer says, and was surely a precursor to today’s mega-dealers with a shop in every port. In other ways, too, Dwan embodied the glamour of the jet age, summering in the South of France and throwing parties at her Malibu home, where artists and collectors mingled by the pool. Predictably, the New York scene was grittier, with Donald Judd and friends holding court at Max’s Kansas City. Dwan owns her own version of the etched window work Michael Heizer did and then redid for the storied bar, after someone threw a brick through it.

Personal collection

Her personal collection, promised to the museum in 2013, comprises the bulk of the exhibition, while additional works round out the picture of what she showed and supported. Edward Kienholz’s Back Seat Dodge ‘38, an assemblage sculpture incorporating chicken wire and beer bottles that shows two figures locked in sloppy embrace, is on loan from LACMA, where the exhibition will travel in spring. Another highlight, The Cliff, features a grid of barely there pencil lines by Agnes Martin, whose solo show will soon open at the Guggenheim. Dwan did not represent Martin (and few other women, for that matter), but included her in “10,” a seminal show of early Minimalism. The aesthetic emerged alongside feminism and civil rights and would eventually fall out of favor for what some saw as its cold refusal to be about anything. Dwan saw an appeal for peacefulness in the works (“It doesn’t get much quieter outside and I think we still need quiet”), but that doesn’t mean her artists agreed with her, or with each other. “We were not able to send you a press release, which would in any way sum up this aggregate of work,” Dwan wrote to The New York Times in 1966 after Robert Smithson, LeWitt, Martin, and the other “10” artists proved incapable of settling on a manifesto.

Keep the doors open

These names were not always so familiar, and Meyer notes that “it’s important to understand that the art tended not to sell.” When Dwan showed Robert Rauschenberg: Combines in ’62, for instance, not a single sale was made. As an heiress to the 3M fortune, Dwan the gallerist could afford to take risks and play the patron, often providing studios or stipends. As she’s said, she knew she could “keep the doors open.” And yet, as all doors eventually do, they closed, in 1971.

Studio and gallery

Afterward, Dwan focused on backing Earthworks, including Walter De Maria’s 35-Pole Lightning Field (a precursor to his larger Lightning Field), for which he planted pointed steel rods in a plot outside Flagstaff, Arizona. Meyer writes that the artist’s impulse to push past the studio and gallery required similar resolve from the viewer. Dwan, of course, was willing to go the distance, often tagging along to help search for potential sites. When Meyer once repeated a joke made by LeWitt, that it’s all science fiction with Smithson, “Dwan grabbed the tape recorder and defended the profundity of Smithson’s work, explaining that it was about geology and prehistory and a kind of timelessness.” Even now, at 84, she displays real feeling for her artists. “I still follow Michael Heizer’s work, Charles Ross, Carl Andre, Anastasi,” she says. “I continue to see them as my concern.”